The article suggests the norms about crafting judicial opinions are gendered and racialized in ways that create higher workloads for women and non-white judges

AMHERST, Mass. – In 1993, the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg made the following statement to the Associated Press about her experience in the legal profession prior to being sworn in to serve on the high court: “When you are the only woman, all eyes are on you.”

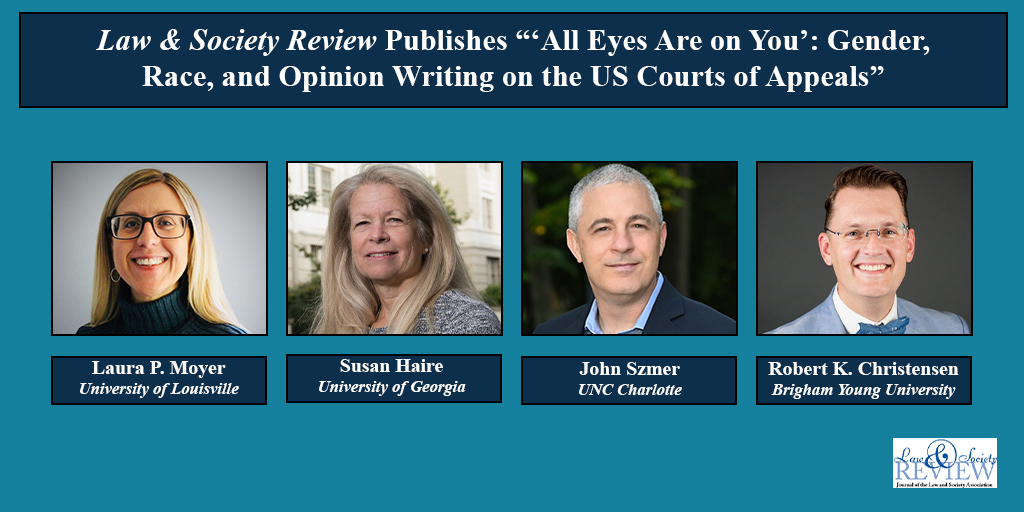

In the current issue of the Law & Society Review (Volume 55, Issue 3), professors Laura P. Moyer (University of Louisville), John Szmer (University of North Carolina at Charlotte), Susan Haire (University of Georgia) and Robert K. Christensen (Brigham Young University) published a study on gender and racial differences between judges when it comes to opinion writing. Their article titled “‘All Eyes Are on You’: Gender, Race, and Opinion Writing on the US Courts of Appeals,” suggests the norms about crafting judicial opinions are gendered and racialized in ways that create higher workloads for women and non-white judges. They discovered that female and non-white judges go farther to explain and justify their rulings, compared to opinions written by their white male counterparts.

“While there is growing awareness of race and gender inequities in society, broadly, we were particularly interested to see how these might affect some of the very institutions involved in resolving equal protection claims: US federal courts,” explained the authors. “We found that courts are not immune.”

Throughout the article, the authors refer to female and non-white male judges as “outsiders” and white male judges as “insiders,” due to the disproportional representation of women and minorities in the legal profession. The authors connect their findings to the adversity “outsiders” face along their path to the bench. Prevailing mechanisms such as stereotyping, impostorism and socialization forces, creates higher pressures to be successful in this “status quo environment” dominated by white male judges—especially on the federal appellate court stage, which decides thousands of cases annually and is only surpassed in authority by the Supreme Court.

They argue that “outsider” judges will strive extensively for perfection in their work to demonstrate they have rightfully earned their position. This work ethic is evident and enduring across one of the most important responsibilities as an appellate judge—authoring opinions for the court. These opinions, which are used to validate and explain legally-sound rulings, will typically be longer, cite more legal authorities and devote more attention to discussing their citations.

In conducting their research, the authors merged case data with information on judicial backgrounds acquired from the Federal Judicial Center. The variables they focused on included page length, the total number of precedents cited in the opinion and the number of cited cases discussed in depth.

“Looking at nearly 3,000 cases decided between 2008 and 2016 in the U.S. Courts of Appeals, we found that women and judges of color go further to explain their rulings and ground them in more legal authorities,” noted the authors. “This is consistent with other research that finds these groups feel a need to work harder to overcome stereotyping and social pressures, especially in elite institutions like courts that have historically had few women or racial minorities.”

They found evidence of the differences between white male judges and non-white judges (male and female) that supported their expectations. On average, white men write opinions that are roughly two-thirds of a page shorter, with almost three fewer cites and one fewer deep citation. Conversely, their opinions are 5.26 percent shorter than those written by women and non-white judges. Female and minority opinion writers include more citations in majority opinions than their white male colleagues. Non-white judges write opinions that have 11.2 percent more citations than those written by white jurists. Appellate judges of color write majority opinions that contain 19.5 percent more deep citations on average than their white peers.

The added workload in this central aspect of judging (opinion writing) may translate into dozens more pages for “outsider” judges than for “insider” judges each year. The study calls for more research to be recorded on other facets of diversifying legal institutions that could determine what changes in organizational practice can create more equitable outcomes.

“Understanding inequities in effort may help to identify measures to prevent work-related burnout,” said the authors. “Our study is one part of a larger NSF-funded project where we are exploring the impact of judicial diversity in federal appellate courts.”

Volume 55, Issue 3 is now available online. It includes six articles and eight book reviews. To read the full LSR article, visit the Wiley Online Library here.

###